Usability Testing of Clinical Research Materials

Adapted from original material created by: Laura Pigozzi, PhD

Usability testing refers to evaluating a product or service by testing it with representative users (www.usability.gov). It is a great way to find out if potential participants understand a research communication, which is why this is a critical part of any health literacy intervention for clinical research. Allowing time for some informal user testing is always better than no testing at all.

Usability testing refers to evaluating a product or service by testing it with representative users (www.usability.gov). It is a great way to find out if potential participants understand a research communication, which is why this is a critical part of any health literacy intervention for clinical research. Allowing time for some informal user testing is always better than no testing at all.

Usability testing provides a way to test clinical trial materials by observing people who are like the study population to find out if content and delivery method will best meet the needs of potential and enrolled participants of a research study. Observation is what distinguishes usability testing from other activities such as focus groups.

This section provides a general summary of usability testing as a health literacy technique and includes sufficient information to guide informal usability testing in the clinical research context.

…usability really just means making sure that something works well: that a person of average … ability and experience can use the thing – whether it’s a Web site, a fighter jet, or a revolving door – for its intended purpose without getting hopelessly frustrated

– Krug, S. (2006). Don’t make me think: A common sense approach to web usability (2nd ed.). New Riders: Berkeley, California.

Planning for a usability test

1. Write Usability Test Goals

Test goals pinpoint what you want to learn and define the purpose of the usability study. For example, you may want to know whether users understand the purpose of the clinical trial or the study visit schedule and clinical trial procedures.

2. Create a Usability Test Plan

This section will focus on informal testing, Barnum (2011), contains information on formal usability testing. Checklists are important to ensure tests are run consistently across participants. Krug (2010) provides useful checklists here. A usability test plan includes the following:

- There are a variety of testing types. For example, a performance test would determine whether the user can complete a specific task. Is the user able to follow-through on the study visit schedule or complete any applicable self-reported study assessments?

- Operationalize the chosen test types by creating scenarios. A scenario is a story that sets the context for the tasks you want the users to accomplish. The tasks will be those items that are the most important things a user needs to do or know.

Example scenario for testing a consent form for understanding of the study visit schedule and procedures:

You have been invited to join a research study called ABC. You are invited because you have Type 2 diabetes.

Task: Indicate the section of the document that discusses periodic clinic visits and list what procedures will take place at each visit. How many visits will there be?

Example scenario for testing a consent form for understanding of specific concepts like study medication and randomization:

You are considering joining a research study called XYZ. You are invited because you have high blood pressure.

Task: Describe which treatment you will get if you join the study. Who decides?

Example scenario for testing a trial recruitment flyer:

You have an appointment with your physician. As you take the elevator to the physician’s office you notice a flyer in the elevator.

Task: Who is eligible to participate in this trial?

You can find advice on writing scenarios at these two sites: usability.gov and Nielsen Norman.

- Questionnaires are another tool to gather usability data. Barnum (2011) lists three questionnaire types:

- pre-test – to obtain additional information about the user.

- post-task – to get feedback right after a user completes a scenario.

- post-test – to rate the user’s overall experience, often using Likert scales.

- End-of-sessions interviews are another way to gather data. These are often structured in the form of open-ended questions.

- The end-of-session interview is a place to explore how a participant might carry out procedures required by the trial that are done outside the research setting, for example filling out a study diary or taking a study medication at home.

- A script ensures the usability test is the same for each user. This script includes welcoming the user, handling any necessary forms, gathering demographic data, facilitating the scenarios, and thanking the users.

3. Recruit Users

Recruiting users can be time consuming:

- decide on a user profile in order to identify representative users.

- offer a small incentive to thank users for their time and opinions

Consult this link for additional advice:

Usability is one of the tools available to researchers to ensure efficacy and understanding of clinical trial life cycle materials Usability testing provides a way to test clinical trial materials with people who are like the study population to ensure the content and delivery method will best meet the needs of potential and enrolled participants of a research study. We will refer to people recruited for usability testing as users.

Usability results have the potential to make a communication more effective, thereby increasing comprehension. By learning why and when users are confused or lose interest, a better user experience can be provided, and the accuracy of the information transfer can be improved.

While it is essential for the artifacts to be effective, usability also looks at the user’s satisfaction with the interaction. In clinical research, greater satisfaction with something like the way information is presented in a consent form, can impact participation in a trial, as well as perceptions of clinical trials more generally.

Conducting a usability test

What Happens during a Usability Test Session?

- The facilitator welcomes the user, explains the test session, asks the user to sign the release form, and asks any pre-test or demographic questions. (Release forms and other applicable forms can be found here: gov forms and Krug forms)

- The facilitator gives more details about the process and asks if the user has any additional questions. The facilitator then explains where to start.

- The user reads the task scenario aloud and begins working on the scenario while they think aloud.

- One to three observers take notes of the user’s behaviors, comments, errors and completion (success or failure) on each task.

- The session continues until all task scenarios are completed or time allotted has elapsed.

- The facilitator either asks the end-of-session interview questions or gives the user a questionnaire to complete, thanks them, provides the incentive (if applicable), and escorts the user from the testing environment.

- The facilitator then resets the materials, checks in with the observers and waits for the next user to arrive

Consult usability.gov advice on conducting a test for further information.

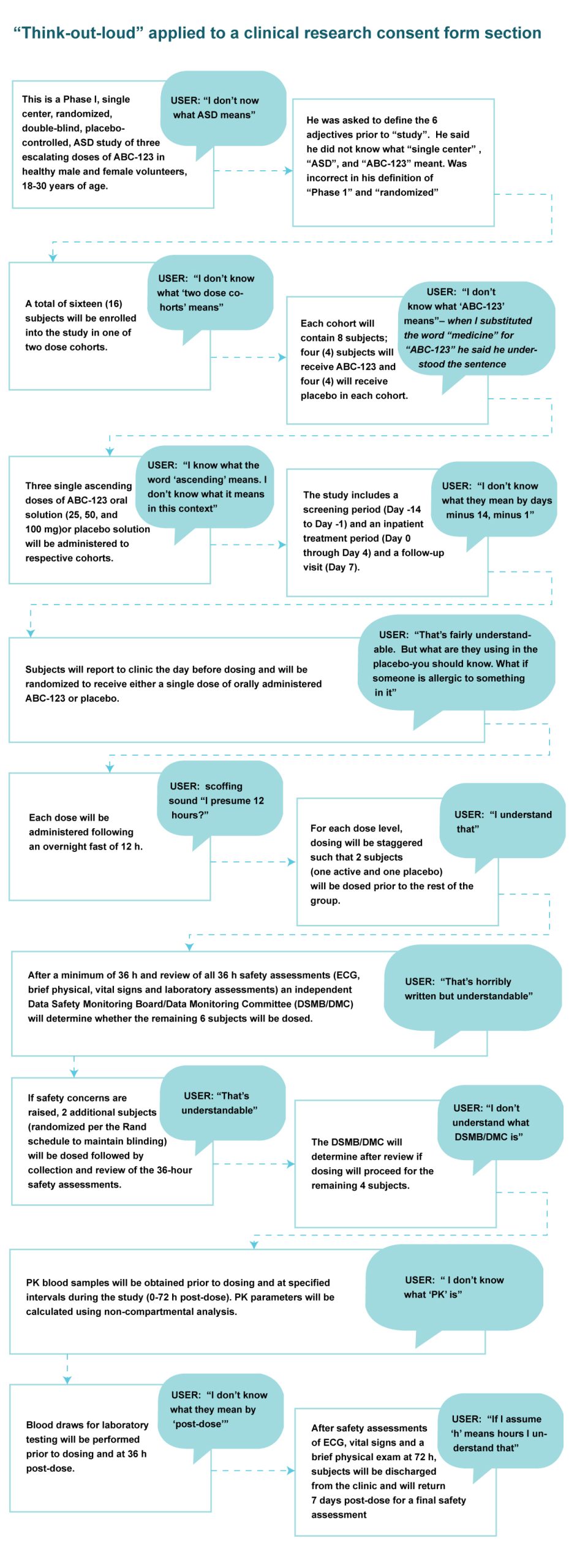

An example of usability in action

“Think out loud” is often used as users work through the scenario tasks. An audio/video example of the think out loud protocol in action can be found here.

Ethics considerations

Usability testing is typically a quality improvement activity but IRB review of your specific testing process may be needed at your institution.

When in doubt, check with your IRB!

Regardless, providing users with a release form for usability testing is a good practice.

Usability Resources

2. Stoplight Coding

Focus-group testing of the template with people having low and average health literacy using a method called stoplight coding:

Focus group participants circle in red what is too hard, highlight in green things that are easy, and highlight in yellow the content that made them pause.

For more on Stoplight Coding, see KB Hadden, et al, The Stoplight Method: A Qualitative Approach to Health Literacy Research, HLRP: Health Literacy Research & Practice, e18